Many modern SaaS products advertise “native integrations” on their homepages as an important feature — but what is native integration really, and how far does it scale? Marketing automation platforms, CRMs (customer relationship management), ITSM tools, developer platforms – they often promise to connect seamlessly with the rest of your stack.

But when you start evaluating options for serious, production‑grade integrations – especially around tools like Jira, ServiceNow, Salesforce, HubSpot, or other popular tools – it quickly becomes clear that not all integrations are created equal.

This article breaks down:

- What native integration actually means

- How native integrations work under the hood

- The benefits of native integrations and their drawbacks

- Examples of native integrations in tools like Jira, ServiceNow and HubSpot

- Where third‑party integration tools, embedded iPaaS and unified APIs fit in

- How to decide between native vs third‑party

.png)

What Is a Native Integration?

When people ask “what is native integration?”, they usually mean “the easy one”. The button in the settings that lets you connect two products in a few clicks, without talking to developers. But that convenience hides a more specific definition.

A native integration is a way of connecting software applications that is built and maintained by the primary software provider itself, and exposed directly through the application’s standard interface. You don’t install a separate connector from another vendor, you don’t write any code, and you don’t need a separate integration platform. The integration is treated as part of the product, not as an add‑on.

Under the hood, this is still an API‑based integration: the vendor uses its own application programming interface (and often the other tool’s API) to move data, trigger actions and keep systems in sync. But all of the complexity of those API connections is wrapped in a user‑friendly setup flow: a few configuration screens, maybe a toggle or two, and you are done.

It’s also important to separate “native” from “cloud‑only”. Native integrations are not limited to SaaS tools or cloud‑based software solutions. You can have:

- Native integrations between two cloud applications,

- Native integrations between two On‑Premise or Data Center deployments,

- Hybrid setups where a vendor‑supplied connector or agent runs inside the customer’s infrastructure and is configured from the product’s own UI.

This is why many SaaS companies treat providing native integrations as part of their core product strategy. They commit to owning the entire integration lifecycle – from initial design and testing, through day‑to‑day monitoring and updates, to eventual deprecation – so that customers experience these integrations as a natural extension of the product instead of a separate project.

How Native Integrations Work

In practice, native integrations usually follow the similar process as any other technical connection; the difference is who owns that process, and sometimes the level advancement of such data synchronization.

From the technical point of view, a native integration is usually implemented as a small, focused integration solution that sits between two systems and automates a specific set of scenarios. It relies on direct API connections, webhooks and sometimes message queues to move data between systems at the right time.

Typically, the entire integration lifecycle looks like this:

- Authentication and authorization

The integration authenticates against the external tool using OAuth, API tokens or service accounts. Permissions are often mapped automatically so that only the intended data can flow.

- Event‑driven or scheduled triggers

The integration subscribes to events (for example, “ticket created”, “issue transitioned”, “meeting scheduled in Google Calendar”), or runs on a schedule (“sync all updated records every five minutes”). These triggers mark the start of each run of the integration.

- Mapping and transformation

The integration translates one system’s data model into the other: fields, statuses, sometimes objects. This might be predefined by the vendor, or configurable by the user. Even when it’s hidden, there is always a mapping layer that governs how data flows.

- Error handling and retries

Because the vendor controls both the application and the integration, they can implement sane defaults for API management: throttling, backoff and retries, logging, monitoring, and graceful handling of changes in the third‑party APIs they call. This is part of what makes native integrations feel “stable” compared to improvised custom integrations.

What makes them “native” is not the technology, but the ownership. The vendor’s own engineers build and maintain these flows, and their support team is responsible for helping you when something goes wrong. Your own development team does not need to build or maintain this particular integration.

Benefits of Native Integrations

Once you understand what native integration is on a technical level, it’s easier to see why almost every SaaS vendor invests in building at least a few integrations for their tools. For many teams, native integrations are the first and most natural way for connecting applications because they remove a lot of friction from the integration process.

The core idea is simple: instead of asking your developers to design and maintain custom integrations, the vendor gives you ready‑made, tightly‑coupled integrations that you can switch on from the product’s own settings. That has several practical benefits.

Fast time‑to‑value

Native integrations shorten the path from “we bought this tool” to “it works with the rest of our stack”.

You don’t need to learn how to use low‑code tools, and you rarely need to write code. In most cases, an admin or power user can:

- Authorize access between systems,

- Pick which objects and fields should sync,

- Turn the integration on.

For teams that are already overloaded, this is a big win. Marketing and customer‑facing teams can connect their software systems on their own, instead of waiting weeks for building integrations by engineers.

Less custom integration work

Every custom API integration looks manageable on paper: connect to an endpoint, map a few fields, handle errors. In reality, they add up quickly. Development teams end up owning a growing network of scripts and services just to keep tools in sync.

With native integrations, most of this is handled for you:

- The engineers take care of the underlying application programming interface calls, pagination, retries and error handling.

- They monitor and update the integration when their own API evolves.

- They provide documentation and technical support that matches how the integration is supposed to be used.

You still own the business logic around when and why you integrate systems, but you don’t have to reinvent the plumbing every time.

Operating inside a single ecosystem

Native integrations shine when you use several tools from the same provider. In those cases, the vendor can design them as if they were one product, not separate applications.

That usually means:

- Shared permissions and identity,

- Consistent UX for configuring and using integrations,

- Data communication in a predictable way between applications.

For example, in a SaaS suite that includes CRM, helpdesk and marketing automation, native integrations often give you a near‑real‑time view of the customer journey without touching an external platform. This helps reduce data silos within that vendor’s ecosystem and gives you better performance than ad‑hoc connections built later.

Risks of Native Integrations

The strengths of native integrations come from their focus: they are built around one vendor’s view of the world, a limited number of external tools, and a curated set of use cases. That focus is also where the significant drawbacks appear. If you rely only on native integrations as your integration strategy, you can easily run into blind spots – from limited coverage and functionality to governance and security issues.

Limited coverage and integration gaps

No vendor can realistically offer native integrations with every other tool on the market. Most will prioritize:

- Their own products, where tight coupling helps reinforce the platform, and

- A shortlist of widely used external tools that are strategically important to their customers.

If your tech stack includes more niche applications, home‑grown tools or legacy systems that don’t fit into modern SaaS patterns, you’ll often discover there is no native integration at all. At that point:

- Critical data stays in silos,

- Teams fall back to manual exports or ad‑hoc scripts, and

- You eventually need other integration tools – a third‑party integration platform, custom connectors, or both – to close the gaps.

This is not just a convenience issue. Gaps in coverage make it harder to standardize your integration process and harder to guarantee that important workflows always behave the same way.

Functional limitations and brittle workflows

Native integrations are meant to be easy to understand and safe to maintain. To achieve that, vendors tend to design them around a standard, opinionated path:

- Send a ticket or task when something happens,

- Sync core records and a limited set of fields,

- Update a status when an external event occurs.

For simple workflow automation, that’s perfectly fine. But as soon as you need more sophisticated behaviour, the integration can turn into a bottleneck. Common requirements that stress native integrations include:

- Complex mappings across multiple custom fields and objects,

- Multi‑step workflows that span several systems at once,

- Heavy transformations, routing or conditional logic,

- Fine‑grained control over the integration lifecycle (scheduling, throttling, retries, rollbacks).

If the native integration doesn’t support this level of configurability, you have a few options: build a parallel custom integration, accept a reduced version of your desired process, or try something that is purpose-built for integrating.

Security and compliance risks

At first glance, native integrations can feel safer than third‑party tools, because they live inside a product you already trust. In practice, they introduce their own set of security and compliance considerations.

A few patterns are worth calling out:

- Hidden data flows. When an integration is just a toggle in the settings, it’s easy for teams to enable it without fully understanding what data moves where, and under which legal or contractual framework. Over time, you can end up with sensitive data flowing between systems with very little documentation.

- Limited visibility and auditability. Many native integrations don’t expose detailed logs or central dashboards. Security and compliance teams may struggle to answer basic questions: who enabled this integration, which records are synchronised, what happens if something fails? That lack of observability makes incident response and forensic analysis harder.

- One‑size‑fits‑all security. Because native integrations must work for many customers, they often make broad assumptions about encryption, key management, and storage locations. If your organisation has strict requirements around data residency or segregation of duties, you may find that you cannot tune these aspects in the way you need.

- Expanded blast radius. The tighter the integration between products, the more careful you need to be about identity and access management. Misconfigured permissions or tokens can unintentionally grant access across several systems at once. A compromised account in one product can become an entry point into everything it integrates with natively.

None of this means native integrations are inherently unsafe. But it does mean they need to be treated as part of your overall security and compliance posture, not as harmless convenience features.

Less control and more lock‑in

Finally, there is the strategic risk of control and lock‑in. With a native integration, you largely accept the vendor’s view of how systems should connect. You have limited influence over:

- How often integrations run and how they scale,

- Where data is processed, logged and stored,

- How errors are exposed and handled,

- Which edge cases are supported and which are not.

As your reliance on a vendor’s ecosystem grows, your workflows start to depend on these choices. The more you lean on proprietary native integrations between a vendor’s products, the harder it becomes to swap one of those products out. You’re not just replacing a tool; you’re unwinding a piece of your integration fabric and potentially re‑implementing it elsewhere.

For some companies, these trade‑offs are acceptable and offset by the convenience and speed of native integrations. For others – particularly those with complex architectures or strict regulatory requirements – they are a strong argument for owning more of the integration layer themselves, either through a central integration platform or specialised tools that offer deeper control.

Examples of Native Integrations in Practice

Talking about native integrations in the abstract is useful, but it becomes much clearer when you look at how specific platforms implement them. ServiceNow, HubSpot and Atlassian all lean heavily on native integrations, though they do it in slightly different ways.

ServiceNow: IntegrationHub as a native platform

In ServiceNow, native integrations are not just a list of one‑off connectors. The platform includes IntegrationHub, a capability that acts as ServiceNow’s own integration engine.

IntegrationHub ships with “spokes”: pre‑built integrations to tools such as Salesforce, Microsoft Teams, Slack, Jira and many more. Administrators use a low‑code designer to build flows that react to events in ServiceNow and call out to these systems. Everything – configuration, execution, monitoring – happens from within the ServiceNow interface.

From the customer’s perspective, this still looks and feels like native integration. ServiceNow’s own engineers build and maintain the spokes and take responsibility for keeping them working as their APIs and those of their partners evolve.

HubSpot: CRM, marketing and sales in one place

HubSpot offers a different, go‑to‑market focused example. It positions itself as a central platform for marketing, sales and customer success, and native integrations are one of the ways it delivers that promise.

Certain integrations, such as the Salesforce CRM sync or connections with Gmail, Outlook and Google Calendar, are so central that they feel like part of the core product. Users enable them via HubSpot’s own settings, and from that point on the integration becomes part of everyday work: logging emails, scheduling meetings, syncing contacts and deals.

Again, HubSpot’s team builds and supports these integrations. Users don’t think of them as a separate integration project. They are simply part of “how HubSpot works”.

Native Integrations for Jira

Jira is a particularly interesting case, because it sits at the centre of many development and operations tech stacks. When people ask “what are native integrations for Jira?”, they are often trying to understand how far they can get with Atlassian’s own ecosystem before they need other integration solutions.

What counts as native in Jira

In the Jira world, a native integration usually means:

- Built and maintained by Atlassian, as part of the product or the Atlassian platform,

- Enabled and configured directly from Jira’s own settings,

- Visible in Jira’s UI without installing any additional Marketplace apps.

These integrations often focus on Atlassian’s own products and a handful of external systems where deep, first‑party integration makes sense.

Jira and Bitbucket

The integration between Jira and Bitbucket is a clear example. In Atlassian Open DevOps, Jira and Bitbucket are connected so that:

- Developers can create branches and pull requests that automatically link back to Jira issues,

- The Jira issue view shows a Dev panel with associated branches, commits, builds and deployments,

- Status changes in Bitbucket pipelines can influence how work is visualised in Jira.

All of this runs through API‑based integration under the hood, but the configuration, permissions and troubleshooting sit firmly in Atlassian’s domain.

Jira and Confluence

The connection between Jira and Confluence is another native integration that many teams depend on:

- Product managers and analysts capture requirements and decisions in Confluence and create Jira issues directly from those pages,

- Engineers and stakeholders see live Jira data embedded into Confluence pages,

- In Jira Service Management, Confluence can serve as a knowledge base that supports deflection and faster resolutions.

Again, there is no separate “connector” to deploy; it’s part of the way the Atlassian platform is designed.

Jira Service Management, Opsgenie and Atlassian Access

For IT service management, Atlassian weaves several products together natively:

- Jira Service Management includes Opsgenie’s alerting and on‑call capabilities, tying together incidents, alerts, escalations and post‑incident reviews,

- Atlassian Access adds centralised identity, SSO and user provisioning across Jira, Confluence and the rest of the suite.

These native integrations are one reason many engineering and IT teams are willing to standardise on Atlassian for key parts of their toolchain: they get a coherent, integrated experience without heavy integration work on their side.

Of course, Atlassian can’t integrate natively with every tool its customers use. Jira is frequently connected to ServiceNow, Azure DevOps, Salesforce, ClickUp, Notion, Zendesk and many others – and this is where native integrations stop and third‑party solutions start.

Third‑Party Integration Tools and Platforms

As soon as your Jira project needs to talk deeply with a system outside Atlassian’s portfolio, you’re usually in third‑party territory. That doesn’t just mean “an app from the Marketplace”; it can also mean broader platforms or embedded iPaaS solutions, no-code and low-code tools.

Why third‑party options exist

Third‑party platforms that synchronize tools step in where native integrations are missing, shallow or too rigid. They aim to give you:

- Wider coverage across different vendors and types of software applications,

- More flexibility over how data moves and how workflows are stitched together,

- A consistent way to manage integrations across your stack.

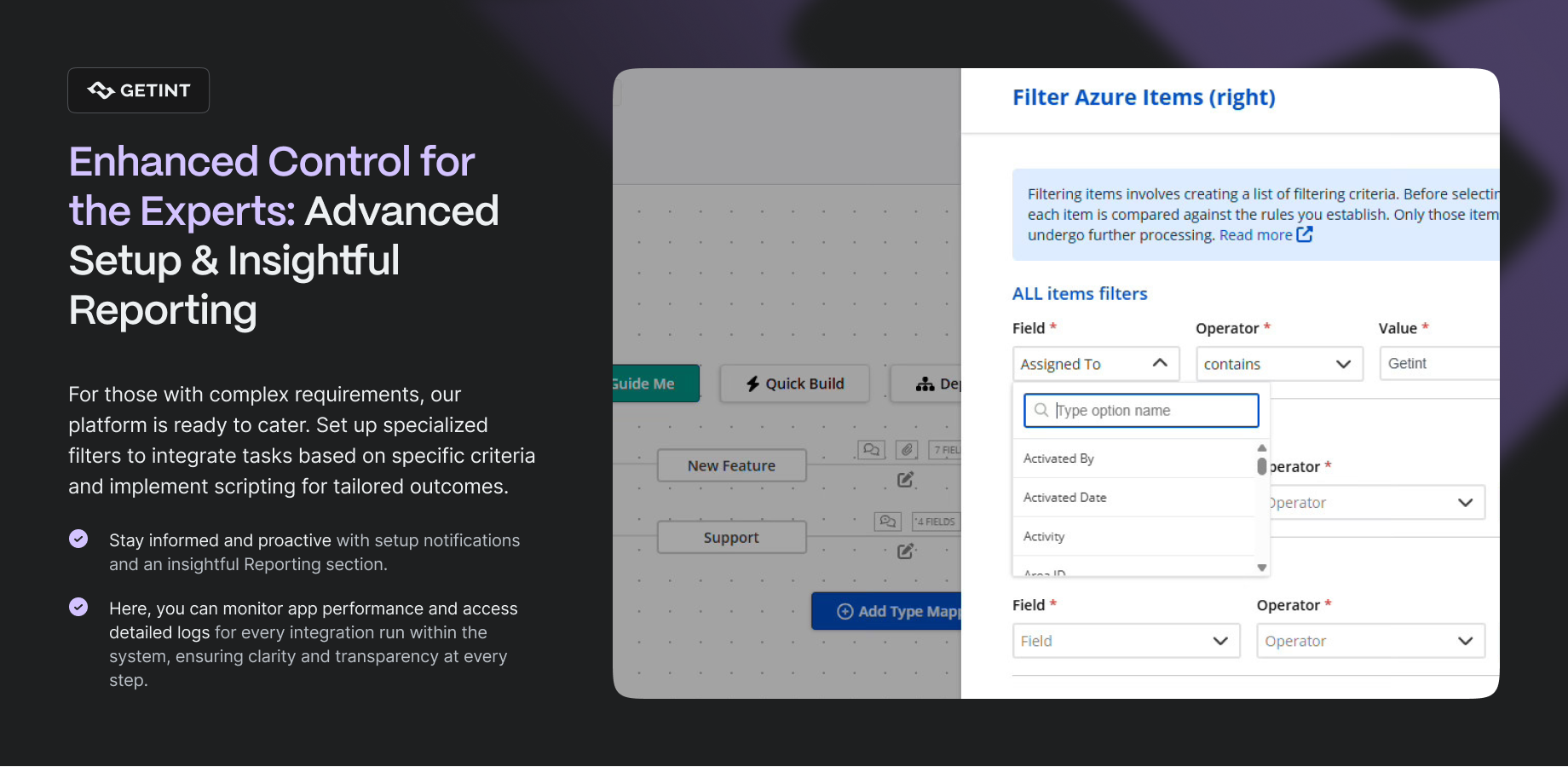

Some are broad iPaaS platforms that focus on connecting almost anything to anything. Others specialize in specific domains. Getint, for example, focuses on deep integrations and migrations across Jira, ServiceNow, Azure DevOps, Salesforce, ClickUp, Notion and other work management and ITSM tools. It provides pre‑built connectors and additional, low‑code configuration when needed, but is independent of any single parent company.

Embedded iPaaS and unified APIs

There is also a growing middle ground where vendors use embedded iPaaS or unified APIs behind the scenes:

- Embedded iPaaS allows a SaaS vendor to present a gallery of “native integrations” in their UI, while an external integration engine actually handles the data flow and orchestration,

- Unified APIs provide one normalized interface to a whole category of tools (for example, many HR systems or ticketing systems), simplifying the work for development teams who are building their own integrations on top.

In both models, the integrations still look native to end users – they are configured in the product’s own admin screens – but technically they live on a dedicated integration layer that is more flexible and easier to evolve.

Choosing Between Native and Third‑Party Integrations

The decision between native integrations and third‑party tools is rarely a strict either‑or. In most organizations, you need both. The real question is where to use each. A helpful way to think about it is in terms of scope and control.

When you are connecting tools that live in the same ecosystem and your needs are relatively standard, many native integrations are usually the best solution. They deliver fast value, minimise integration development and give non‑technical teams a way to integrate systems themselves. Typical examples are Jira with Bitbucket and Confluence, or ServiceNow with its main spokes.

As your architecture grows and you start connecting more tools from more vendors, the picture changes. If you rely on Jira and ServiceNow plus several CRMs and marketing tools, and you need them all to share data reliably, it becomes time-consuming, and very hard to coordinate everything through separate native integrations alone. A third‑party software can give you a single place to design data exchange, monitor and evolve those connections with complete control.

Finally, you need to consider how much control and governance you require. Native integrations are convenient, but they spread your integration logic across many products. If you work in a regulated industry, or if you simply want a clearer view of how data moves through your organization, centralizing more of that logic in a specifically designed platform like Getint often makes more sense while protecting from unexpected security threats.

In practice, many teams end up with a pattern like this:

- Use native integrations for basic needs, where they are strong and aligned with your architecture (for example, within the Atlassian or ServiceNow ecosystems),

- Use specialist integration solutions where you need deeper, bidirectional sync or complex migrations between tools,

- Reserve fully custom API integrations for truly unique scenarios that neither native nor third‑party tools can handle cleanly.

That balance lets you take advantage of the convenience and speed of native integrations without losing the flexibility and control you need for evolving business and growing technical resources.